The family lore that my grandmother held in the highest esteem involved the early joiners of the Mormon Church, the relatives who followed the Saints west to establish a utopia in the desert wilderness. They were adventurous and brave, she told me, the toughest of the tough, and unbending in their faith. As a second-grader in 1986, I was delighted whenever my class filed into the school computer lab. We’d insert our floppy discs into Macintosh 128Ks and stare wide-eyed as the black and green world of The Oregon Trail came alive. I liked to believe I was living out the story of my forebearers, fording rivers and shooting pixilated animals until I died of dysentery. In church, I’d join my primary class in singing “Pioneer children sang as they walked, and walked, and walked, and walked, and walked ….”

As far as I remember, the verse about walking keeps going. It sounded like a dream, even as a child. Little did I know I’d follow this strange dream into my adult life — to walk, and walk, and walk in an insatiable pursuit of adventure.

So the stories I recently found about my great-great-great-great grandfather, Russell King Homer, were particularly satisfying. However, I should include a disclaimer that these stories are typical of 19th-century Mormons. Content warning: Colonization of Native American lands, disrespect of their remains, polygamy, etc. …

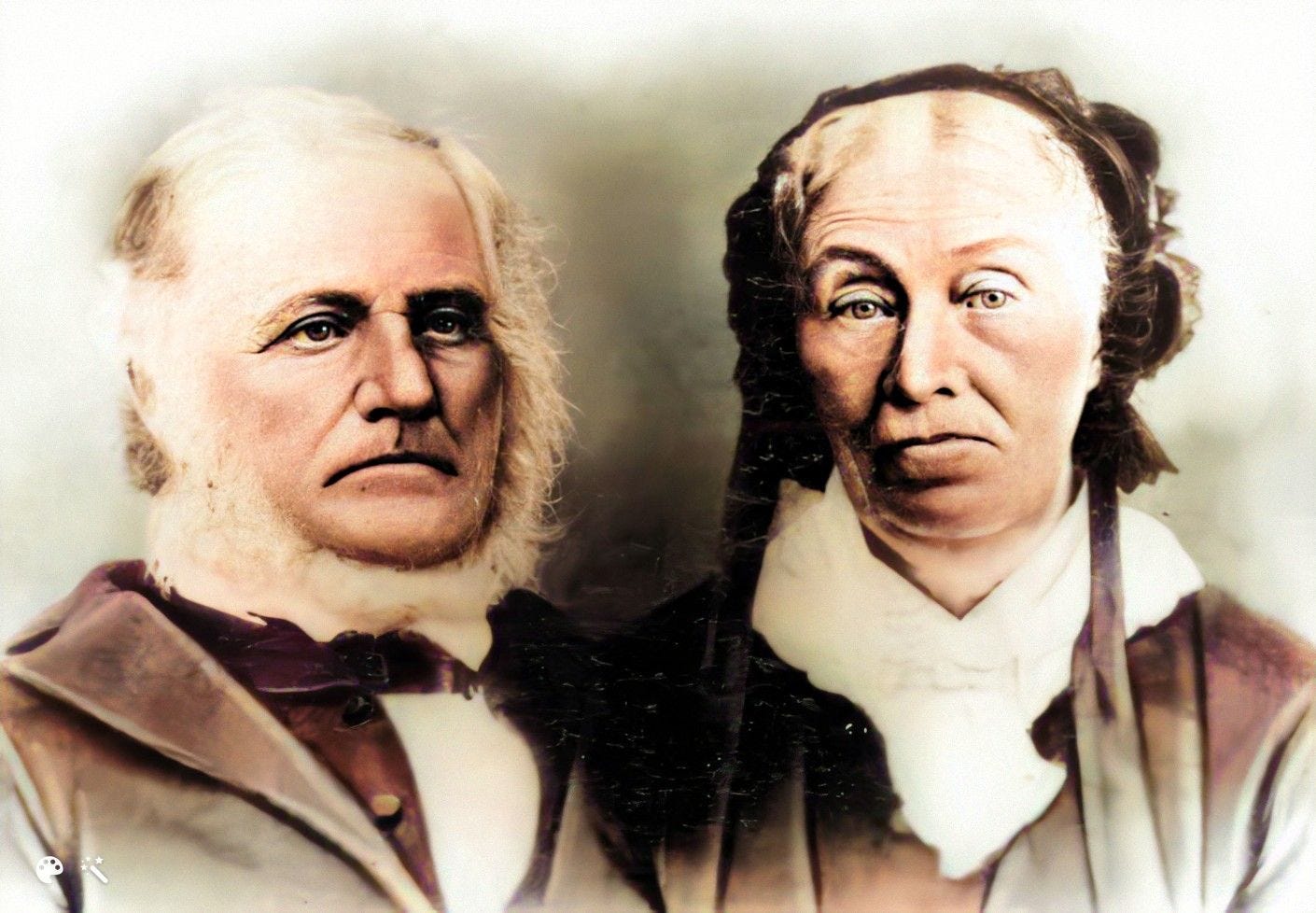

Russell was born July 15, 1815, the fifth of nine children to Benjamin Cobb Homer and Anna Warner. As a child, he was fair-haired with a prominent nose and striking blue eyes that strangers would remark on. The family lived on a homestead in Onondaga County, New York. Russell’s childhood was similar to most pioneer children of his time — hard work and farm chores with few luxuries. When he did find time to play, Russell enjoyed hiking through the forest and searching for bones. Scattered on the ground throughout the woods were human bones, which Russell believed belonged to Native Americans who died in wars before Europeans arrived in that part of New York. He often invited a neighbor girl, Eliza, to join these expeditions.

When Russell was 15 years old, he and several other boys were riding horseback when they encountered a stranger in the woods. The stranger, a man in his mid-20s, was described as “a handsome man on a magnificent black horse, and his whole appearance was so striking that they were amazed.” The man asked Russell for directions.

“My boy, what is your name?” the man continued, and Russell answered.

The stranger replied, "My name is Joseph Smith, and my boy, you will join the church that has just been organized, and go with the Saints to the Rocky Mountains and stand up and bear your testimony to the truthfulness of the everlasting gospel."

(The veracity of this story is somewhat suspect. The year would have been 1830, the same year Joseph Smith established what was then called The Church of Christ — later The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — in Fayette, New York. It’s unlikely he knew then about his fledgling church’s future in Utah. However, Fayette is near Onondaga County and it’s plausible that Russell met Joseph Smith in 1830.)

Russell and Eliza were described as “childhood sweethearts.” When Russell’s family moved to Crawford County, Pennsylvania, following the unsolved disappearance of his eldest brother, Eliza’s family also relocated nearby. Russell and Eliza married on December 20, 1836, in Erie, New York, when both were 21 years old. They spent the holidays honeymooning at Niagra Falls. They rode the first steamboat to sail on Lake Erie, a luxury for which Russell had to spend the last of his money. He sold his boots to procure sufficient funds to complete the journey home.

Their first home in Pennsylvania was a log cabin cut from the clearing where the house stood. The house had a central fireplace with a single iron pot for baking and cooking. As they had no matches, starting a fire was difficult, so they tried to keep the fire burning at all times. Eliza or Russell would watch it all night to keep it under control. On one occasion, Russell had to walk seven miles to find a flame, which he carried with him in an iron pot, keeping it alive by occasionally replenishing it.

In 1838, the couple gave birth to a daughter who lived only a few days. Three weeks before the eldest son, Edmund, was born in 1839, Russell walked outside one morning to do his chores and heard a faint cry emanating from what looked like an empty crate. He was shocked to find a baby boy who couldn’t have been more than a few days old, wrapped in a tattered blanket. At the infant’s side was a note stating that his father was dead and his mother was unable to care for him. Russell and Eliza fell in love with the child and kept his given name, “Edson,” hoping to pass him off as Edmund’s twin brother. But when Edson was three months old, a young woman appeared at the doorstep with her brother. She claimed she had been engaged to marry the child’s father. On the day of their wedding, the man attempted to cross a river that divided their homes. But the water was high and swift, and he drowned. The woman’s brother had been away and knew nothing of his sister’s trouble, but now that he was aware, he felt it was his duty to raise and educate his nephew. Because the woman had proper credentials and a notarized receipt, the Homers had no choice but to give up their adopted child.

Several months later, a stranger knocked on their door and asked for a night’s lodging. Russell welcomed him and followed the man outside to help unhitch his wagon. The man took a book out of his wagon and said, “I think your name is Homer. Here is a book your friend Martin Harris sent you.” The book was an early copy of The Book of Mormon. As Russell recalled in his later years, a voice said distinctly in his ear, “That is a history of those bones you used to play with.” When he called out to the man to ask him to repeat what he said, the man looked confused and replied, “I said nothing.” Russell read the book and became convinced it was a true account of ancient civilizations in North America and the word of God.

Russell immediately longed to travel to the headquarters of the Mormon Church. He convinced his wife, her sister, and her sister’s husband to join him on a trip to Kirtland, Ohio. They were not interested in joining a new religion but agreed. They arrived to find a congregation gathered around Joseph Smith, who was giving a sermon about the church’s poverty. After the session, Russell walked up to shake Joseph Smith’s hand and left a $10 gold piece in it. Joseph Smith praised the donation and promised Russell, “Neither you nor your family shall ever want for bread.” Russell drank in every word of the following sessions and wished to be baptized before leaving Ohio. The others weren’t so impressed, and the family returned home without going through with the baptism.

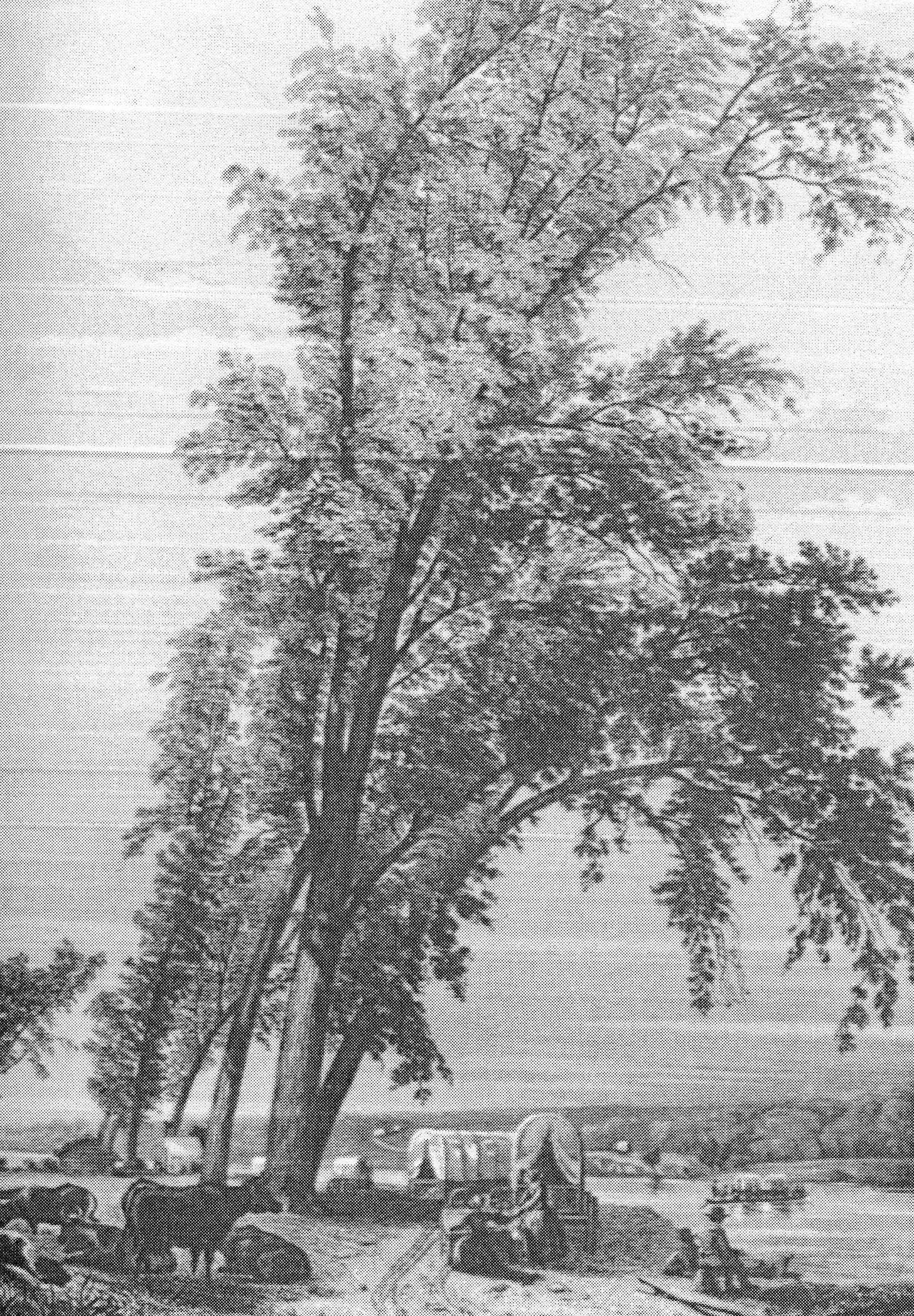

At the time, the tide of emigration was moving westward to Ohio and Illinois. In the spring of 1840, Russell got “a bad case of western fever,” his daughter, Rachel, later wrote in an extensive family history. Russell said he was tired of living where he had to chop down trees to see the sun rise. With the promise of open horizons and opportunities on the frontier, he and Eliza loaded their few belongings in a covered wagon and started west. They lived for several years in Logan County, Illinois, where their next two children, Nancy and Anna, were born.

When the Mormons established the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, the family continued their westward migration. They camped near the present site of Springfield, Illinois, where their fourth child, William, was born in a covered wagon. Russell desperately wanted to be baptized, but couldn’t go through with it until Eliza was on board. She steadfastly refused until 1844, when she suffered a sick spell. Several Mormon elders administered to her, after which she rapidly regained her health. She viewed this as a miracle, and it was enough to change her mind. The couple were baptized together on March 21, 1844.

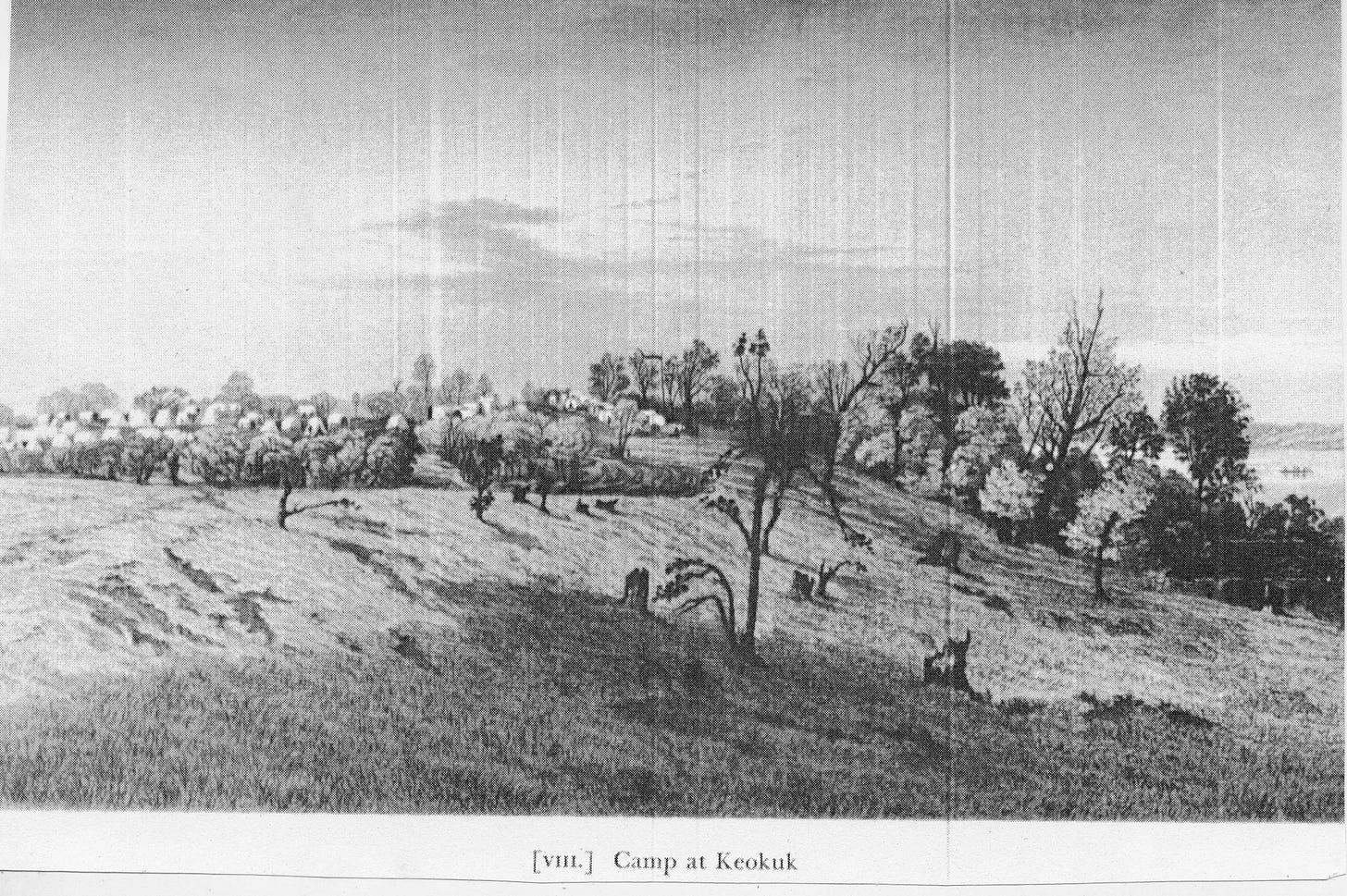

Rachel wrote, “They cast their lot with the Saints for better or worse and cooperated with them in every way to further the cause of the church.” When Joseph Smith was shot to death while imprisoned in Carthage, Illinois, the family joined the Saints in their mass exodus from Nauvoo. They stopped long enough in Garden Grove, Iowa, to plant crops for those who came later. Then they continued to the Missouri River where they lived for several years with the Pottawattamie. The Natives provided the family with corn, beans, melons, and other foods. While living there, Russell established a ferry across the Missouri River. His flat boat propelled by oars was the only means of crossing the river for several years. He later established a mercantile business and opened a post office. Under the council of church leaders, Russell stayed in Iowa to support the Saints as they continued their migration west toward Utah.

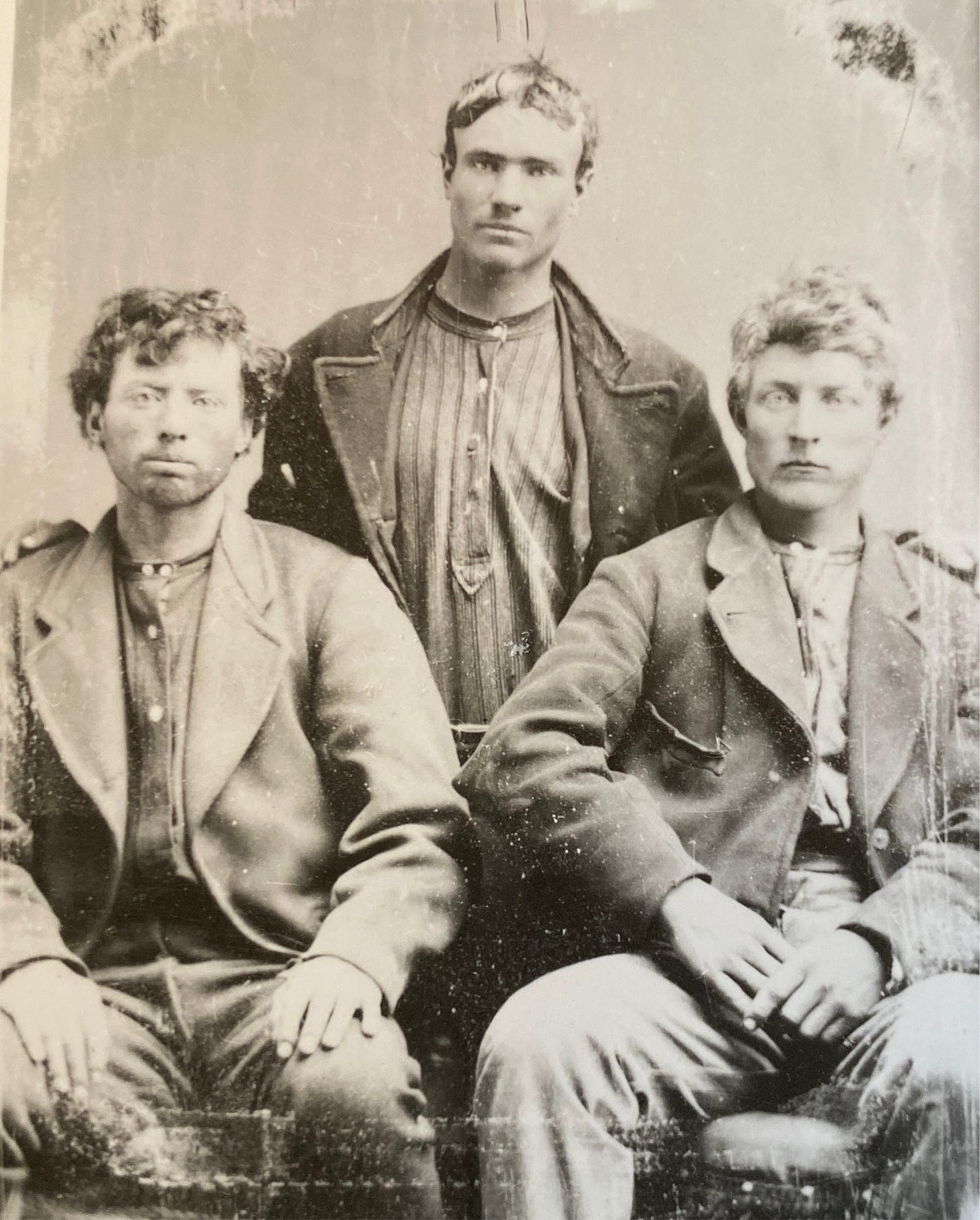

In the spring of 1849, Russell signed a contract to haul freight for the first general merchandise store in Salt Lake City. He took a crew of eight men, expecting to return to Iowa in the fall. Along the way, all nine men contracted cholera, which delayed their schedule considerably. Russell sold the outfit in Salt Lake City and immediately turned around to return to his family using a saddle pony and a pack mule, knowing he had little time to waste to make it home before winter. He was accompanied by other church members who had signed up for missions in Palestine. Somewhere in Nebraska, the group was struck by a terrible blizzard. They stumbled through a whiteout for hours before miraculously coming upon an abandoned cabin. Russell soon fell ill, and they spent several days holed up in the cabin while Russell battled pneumonia. Most of their stock perished. Russel survived, but remained ill and weakened for the rest of his life of what he referred to as “mountain fever.”

In 1852, Russel returned to Pennsylvania to settle the estate of his father, who had recently died. Russell and Eliza’s eighth child, my great-great-great grandpa, Benjamin, was born in 1853 during their time in Pennsylvania. Russell tried to convince his extended family to join the Mormon Church and follow him west. All refused and attempted to counter-persuade him into returning home.

“Father thought Iowa was the garden spot of the world and used to say that nothing but religion would induce him to leave,” Rachel wrote. Russell returned to build a homestead on Pigeon Creek in Iowa. After improving and selling the homestead, they moved to Crescent City to open a hotel called the Homer House.

Patrons of the Homer House were largely Native Americans and Mormon missionaries passing between the East Coast and Salt Lake City. As Russell continued to take contracts to guide pioneer companies to Utah, Eliza stayed in Iowa to run the hotel. She was famously a wonderful cook, and patrons often stayed for days or even weeks. Her neighbors worried about Eliza, “Being all alone in the hotel with all those Indians,” but Eliza assured them that the Native Americans were her friends. In 1857, 16 missionaries arrived too late to continue east with the last company leaving that year, so they stayed with the Homers all winter.

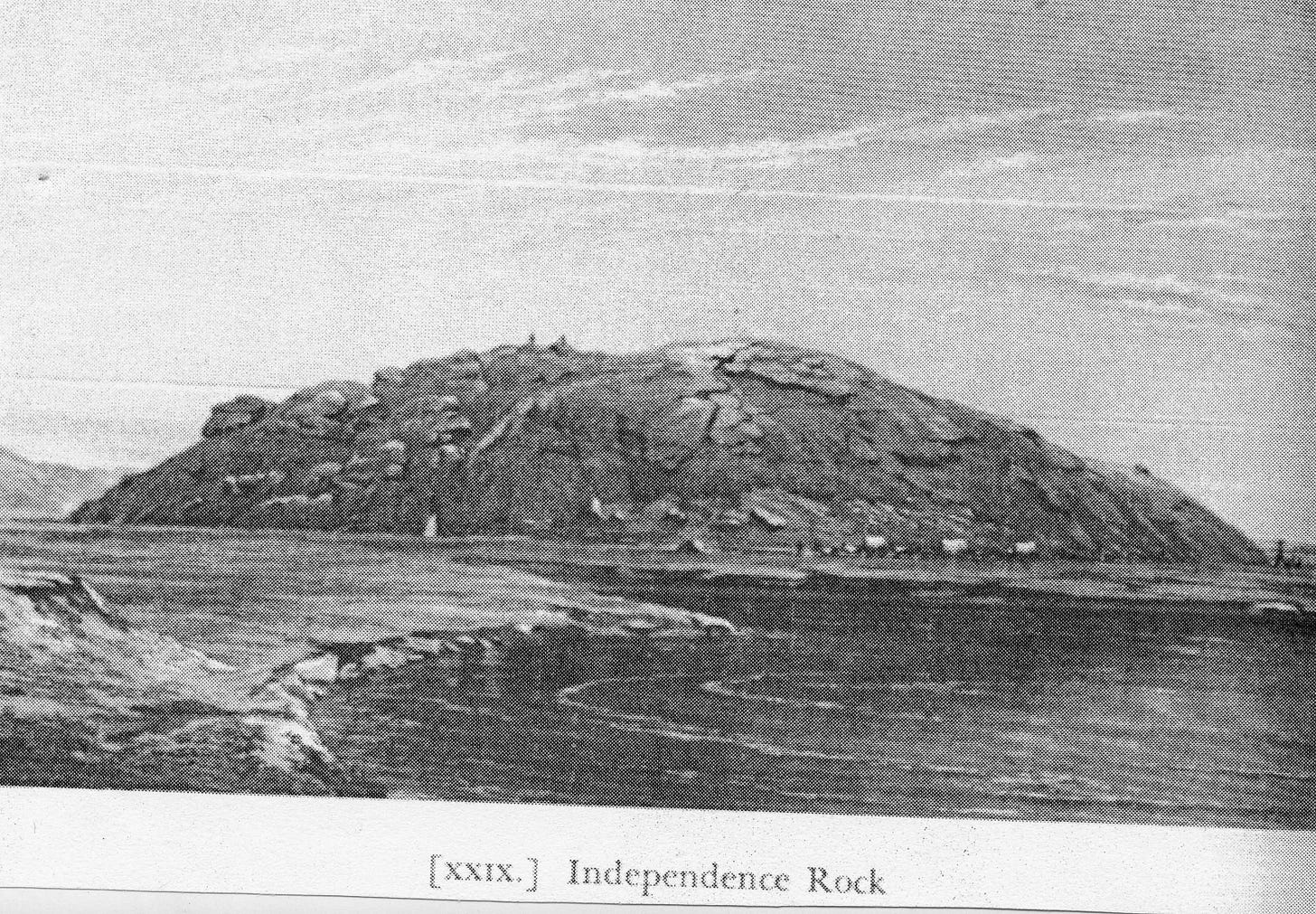

In the summer of 1858, Russel gave up his “garden spot” and joined a Danish company on the permanent trek to Salt Lake City. Russell had amassed considerable wealth as a businessman in Iowa, so he equipped his family with the finest camping supplies, merchandise, horses, mules, and cattle. Early in the journey, they came across treacherously high water but were able to ferry across the river. A few weeks later, a band of Sioux confronted the company. As the Sioux approached, the Danish men grabbed their rifles. Russell told them to back down.

“Sit still!” Russell shouted. “It will be all right. I need a volunteer to carry a white flag out there. You will be safe, I promise you. If they had wanted us dead they would have fired on us by now.”

Russell returned to his covered wagon, changed into his Sunday best, and approached the chief.

“To cross our land you will need to pay us,” the chief said. “We will take fifty bags of flour, twenty bags of sugar, fifty bags of tobacco, and fifty head of your cattle.”

“I see the chief of the Sioux cares for his people,” said Russell. “He desires many goods for his people’s benefit. However, I care for my people as well, and if I were to give you what you ask for my people would soon starve and die. I cannot allow that and still be their chief. I will offer you eight bags of flour, three bags of sugar, four bags of tobacco, and five cattle.”

The Sioux chief rejected the offer as much too low. As the sun moved across the sky, the two men settled in for a long bargaining session that Rachel reported was pleasant and even amiable at times. At about six in the afternoon, they finally reached an agreement. Russell paid the tribe with four bags of sugar, four packets of tobacco, six head of cattle, and several trinkets. The Sioux chief reportedly liked the group and offered to accompany the wagons for several days to protect the company while they crossed the lands of other tribes.

“One night we camped on Wood River, near its junction with the Platte, and had just got our cook tent pitched when it started to rain,” Russell’s 12-year-old son, William wrote. “How it poured down, accompanied by fierce thunder and lightning. Everybody rushed for cover; 16 crowded in the tent. Mother was near the stove cooking. I was on the ground behind the stove. I heard a heavy clap of thunder and the next thing I knew, it was the next day and we were traveling along in the wagon. Mother told me the tent had been struck and everybody in it was stunned. I was the last to come to. Mother was the worst injured. She was badly burned about her feet and legs, her shoes were torn off and her clothing was torn and burned.”

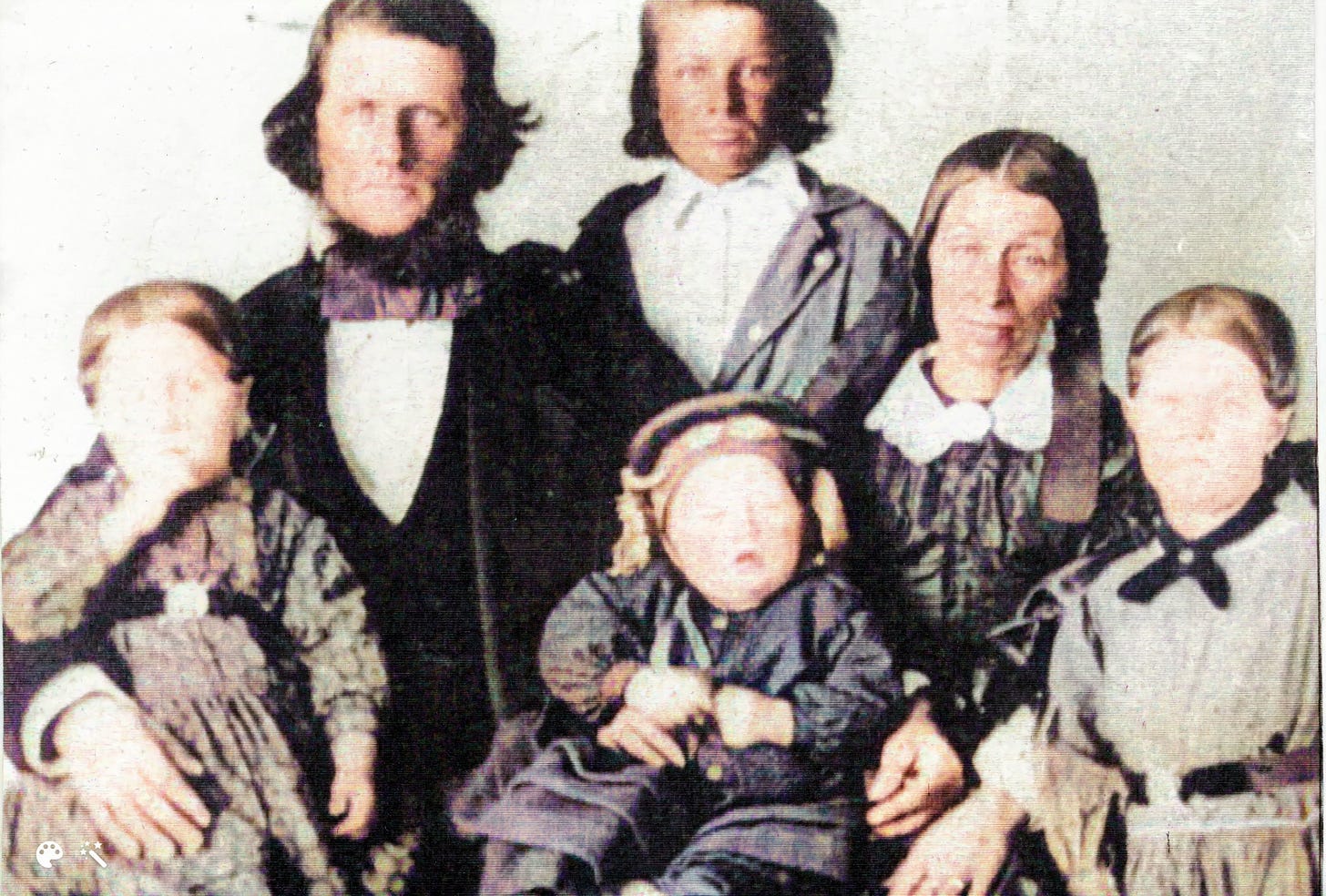

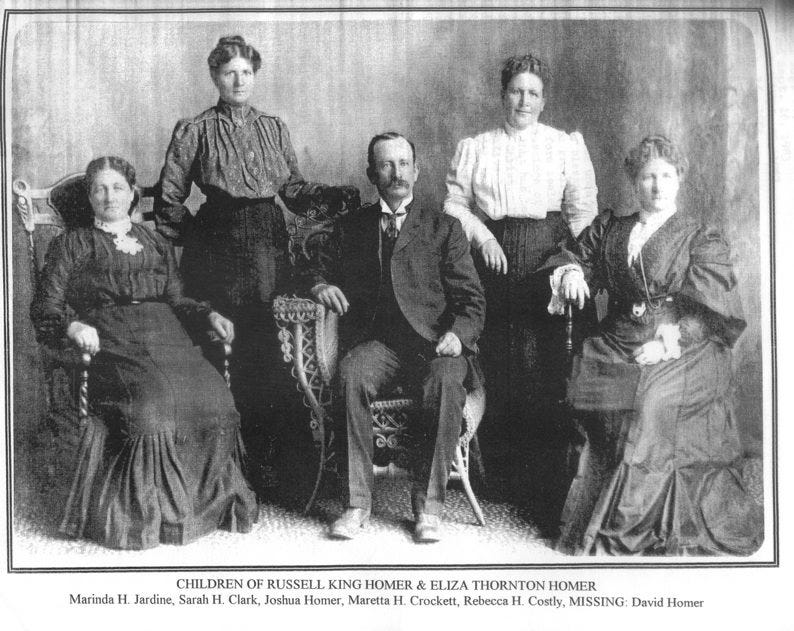

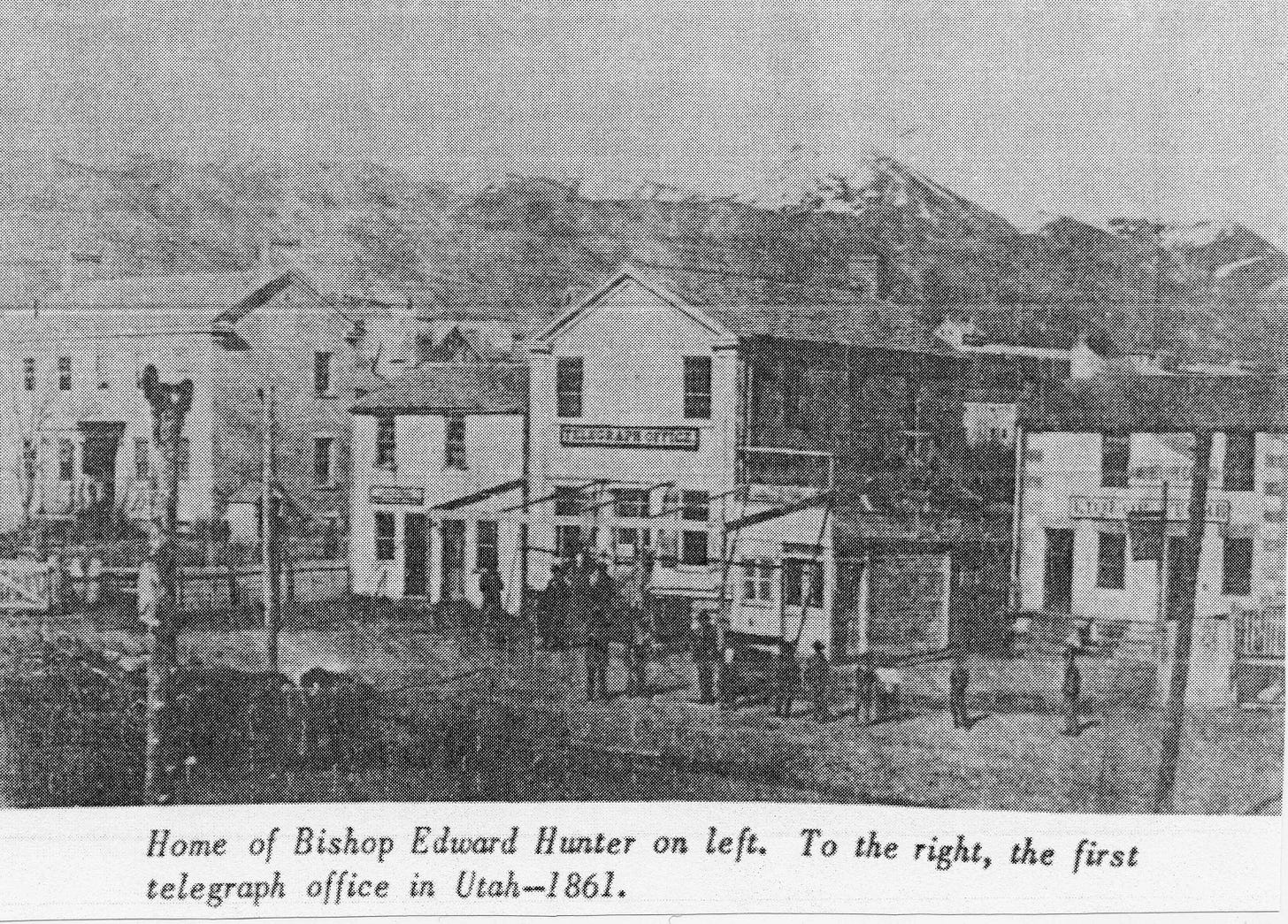

The family arrived in Salt Lake City on Oct. 7, 1858. Their 11th and last child together, Russell King Homer II, was born in 1859. Russell continued to work in freighting, making several trips back and forth across the Plains before he turned over operations to two sons and two sons-in-law. As a man of wealth and good standing in the Mormon Church, leaders advised Russell to marry in polygamy. Soon after settling in Salt Lake, he married two more wives, Mary Anderson and Eliza Thornton.

Russell continued to expand his progeny and holdings in Northern Utah and Southern Idaho. He built a place on the Weber River and served as the first justice of the peace in that part of the country. He also settled in a place that was then called Gentile Valley and another just south of Brigham City, where he established a home with his third wife, Eliza Thornton. The birth of Eliza Thorton’s sixth child happened in mid-winter. No doctor could travel through the deep snow to attend to her. Shortly after the birth, she died of pneumonia. Russell undertook a perilous winter journey to deliver the children to his first wife, twice becoming stuck in the mud and unloading supplies as his young children were forced to walk. The sight of six new children must have been a shock for Eliza, who was by then nearing 50 and had 11 children of her own.

“If she was not happy to see him and the extra burdens he had brought with him, she didn’t say so,” Rachel, the daughter of Eliza Thornton who was 3 at the time, wrote. “She kissed each one of us and gave us a good supper and put us to bed. What a haven that was to us poor wayfarers who had been so long in the mud and rain.”

Eliza Thorton’s children would go on to call her “Mother Homer.”

“Mother Homer was of an entirely different disposition (than Russell),” Rachel wrote. “Most of the time she was very serious and stern in her demeanor. She ran her household industriously and methodically. Her life was regulated by the clock. She did not use slang or show emotion of any kind. She showed the same courtesy to the humble tramp as she did to the highest personage. She had an unusual sense of justice and fair play for everyone, always seeing to it that the underdog was protected.”

Russell set out to find a larger homestead where he could bring his large family together. He settled on the Cache Valley of Northern Utah, a fertile, grassy valley where he could raise cattle and horses, and mow wild hay. In 1874, Russell married a fourth and final time. He also, like his father before him, took an interest in medicine and became the physician, surgeon, “bone setter,” and veterinarian for his neighbors on the frontier.

I loved Rachel’s descriptions of her father, which reminded me of my father and Grandpa Homer:

“About ten years before his death, father bought a light spring wagon,” Rachel wrote. “He drove around the country a great deal, always managing to take a load of his family with him. We were the envy of other children in the town because we got to travel so much, and it certainly made us feel important.”

“Father was the typical pioneer, usually dressed in the true western style with high-topped boots, red and black checkered flannel shirt, pants, a vest, and a Stanton hat. He had bright blue eyes that expressed deep understanding or flashed fire as the occasion demanded. He had a great fondness and affection for children — his own and everyone else’s. The shiest child found himself seated upon father’s knee and all his troubles vanished.”

But with all his loving kindness and consideration for the members of the family, he insisted upon rectitude and propriety in all things. Usually, only one look from those flashing blue eyes was enough rebuke for the boldest culprit, while to be left at home from one of those trips was sufficient humiliation for any transgressor. His punishments were those that hurt the ego more than the flesh. As his children were married and settled down, he made it a habit to see those who lived in town every day. Those who lived farther away he saw enough to know firsthand just how they were getting along.

In 1884, Russel accidentally drove his buggy into a ditch and was thrown onto the ground. He suffered a concussion and fractured both shoulder blades. He never fully recovered from the accident, and his health gradually declined. He died Feb. 12, 1890, at the age of 75. Eliza sold the property in Utah and moved to Rigby, Idaho, close to her youngest son, King. She died in 1912 at the age of 97.

Between his four wives, Russell fathered 24 children, who in turn had 138 grandchildren. This photo of a family reunion in 1900 leaves me to believe that I am related to half of the population of Northern Utah. Such was the way of life during the Mormon pioneer days. It’s wild, isn’t it?

Fascinating family history. And you found all of this information on FamilySearch.org? Makes me want to check it out.

Fascinating, I enjoyed that.