This is my Grandma Homer. She’s probably the toughest, most pragmatic woman I’ve known in my life, from her Depression-era childhood on a family farm to her years-long battle with terminal cancer while living alone. She was fiercely independent to the end, which came on June 9, 2019, when she was 89. Grandma was not a sentimental person, but she was a meticulous keeper of records. If one of her 19 grandchildren did something she was proud of, she collected photos and wrote updates for 19 different “Grandma Angel Books,” which we all inherited when she died. Even though I don’t necessarily agree with Grandma’s standard of ranking achievements, I love this scrapbook because I am a sentimental person.

Grandma also spent hundreds of hours at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Family History Library, combing through centuries’ worth of books, documents, and microfilm to trace her family's origins. One of my regrets is that I didn’t talk with my grandmother about her family history work before she died. Of course, now it’s the digital era and all of this and others’ work lies at my fingertips.

I questioned whether I wanted to go down this rabbit hole, as it is a deep, deep hole. But the election is coming, the October news cycle has been particularly depressing, and I have been feeling bummed out about my health. I greatly need distractions, and FamilySearch.org is a bottomless trove of distractions.

I spent a few nights after work buried in our Family Tree, and what I found already is so interesting! It’s interesting to me, of course, but also interesting from a history-buff perspective. I started with my paternal line because historical record-keeping favors men, and also because it’s fun to learn more about the people who gave me my name. Here’s what I found, so far, about the early Homers:

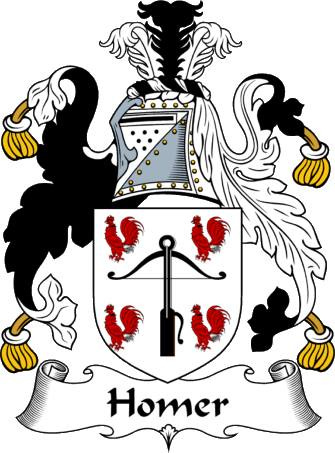

Here’s our family coat of arms. Isn’t it cool? The rooster denotes great courage or a herald of the dawn. The family name reportedly arrived in England after the Norman Conquest of 1066. The name is derived from the Old French word 'heaumier', meaning 'helmet maker'.

This paternal branch of the family tree traces back to my 14-times-Great Grandpa Richard Holmer, born in 1498 in Staffordshire. According to the tradition of the Staffordshire Homers, our ancestor left his lands in Dorset in the fourteenth century after losing a duel. He settled in the county of Stafford, a landlocked region in the western midlands of England. Here, he or one of his descendants built the house of Ettingstall.

There’s not much more than birth, death, and marriage records until Richard’s great-great-grandson, Edward Holmer, was born in Staffordshire in 1598. Sometime during his life, Edward dropped the “l” and took the name Homer. Like his grandfather and father, Edward was a solicitor and held the office of Deputy Steward to the corporation of Sutton Coldfield. (Whatever that means. Most of these early records list only marriages, baptisms, occupations, and receipts for things purchased.)

Edward’s grandson, John, was born in Sedgley, Staffordshire on March 20, 1657. John was one of the earliest Homers to immigrate to America, arriving in Boston in 1672. John was the captain and likely part owner of a large ship that delivered wine and other goods from England to the New World. He didn’t marry until age 45 but went on to have eight children. John is thought to be the patriarch of a large posterity, estimated between 50,000 and 100,000 descendants, including the famous 19th-century landscape painter Winslow Homer and yours truly.

Benjamin Homer, the second son and third of eight children of Captain John Homer and Margery Stevens, was born May 8, 1698, in Boston, Massachusetts. When Benjamin was a young man, a merchant in Yarmouth approached him about a business opportunity making custom clothing for sailors. Benjamin moved to Yarmouth to become a tailor for the merchant. There, he met and married Elisabeth Crowell, bought a farm, built a house, and had six sons and three daughters.

At least four of their six sons (John, William, Benjamin, and Thomas) became seamen like their grandfather. In 1768, the second son, John, joined the Sons of Liberty — a secret, political organization that fought against British taxation. The Boston branch of Revolutionary War-era rebels was responsible for executing the famous Boston Tea Party of 1773. The year John joined, the Massachusetts House of Representatives voted to raise a Committee of Correspondence with other colonies to compile their mutual grievances, which alarmed the British Ministry. The British government instructed Massachusetts Gov. Bernard to contact the representatives and demand the act’s repeal. House members engaged in a lively debate over this demand and voted “Not to Rescind.”

In celebration of this act of civil disobedience, the Sons of Liberty commissioned a massive punch bowl with an inscription to celebrate “The glorious ninety-two Members of the House of Representatives of the Massachusetts Bay, who, undaunted by the insolent menaces of villains in power from a strict regard to conscience and the liberties of their constituents on the 30th of June 1768 voted 'Not to rescind.'“

Fifteen members of the Sons of Liberty had their names inscribed below the rim of the bowl, including John Homer. Housed at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the silver bowl is considered one of America’s most cherished historical treasures.

Although he was apparently a proud Son of Liberty with his name permanently inscribed in the nation’s historical record, John became a British loyalist a few years later. He was among the loyalists evacuated from Boston by the British Navy in 1776. His property was confiscated and his business was ruined, so he and his family escaped to Nova Scotia, where he died in 1799.

“No! Grandpa was a turncoat?!”

But I was wrong about this. In my excitement of researching Captain John’s misplaced loyalties, I misread that branch of my family tree. John was actually my Great-Great-Great-Great-Great-Great-Uncle. His younger brother, Thomas, is my forebearer.

Capt. Thomas Homer was born March 21, 1736, and like many other Massachusetts Homers, he took to the sea in his youth and became a captain. In 1763, he gave up sea roving and settled down as a merchant tailor in East Dennis, near Boston. He married Elizabeth Sears. They had six sons and four daughters. Three sons were lost at sea in youth before they married. The third son, Benjamin Cobb Homer was born on June 24, 1777.

Benjamin Cobb Homer followed in the footsteps of his father and went out to sea when he was still a boy. But soon ill health forced him to give up his sailing career. He moved to western New York to start a farm. There, he met and married Anna Warner, whose grandmother was a Cherokee princess, a fact that Benjamin held in particular pride and reverence. The newly married couple settled in a forested wilderness in Onondaga County, New York.

According to family records, Benjamin and Anna lived a life similar to the story depicted in “Drums Along the Mohawk." (A 1936 novel about a couple who settle on the New York frontier during the American Revolutionary War and defend their farm from Loyalist and Native American attacks before the conflict ends and peace is restored.) Benjamin and Anna cleared the land and used the logs to build a small house and an outbuilding to house livestock and chickens. The buildings were chinked and daubed with mud and covered with a heavy coating of brush and dirt to keep out the heat and cold, and also to protect from attacks. Their family of nine children was well-fed: The woods were full of game, and they planted vegetables and corn. They raised sheep to provide wool to spin and weave for clothing and bedding. Anna cooked all of their meals over the fireplace in the center of their home, and taught her family to read and write with the only book they owned, the family Bible. She also served as a maternity nurse for their scattered neighborhood. She would answer any call she received, walking narrow trails in terrible blizzards to attend to a woman in need. Benjamin studied animal medicine and became the only veterinarian in that part of the country.

Joshua, their eldest boy, left home when he was 20 and disappeared. Much speculation and years of effort went into locating him, but his disappearance is a mystery that has never been solved.

Heartbroken, Benjamin and Anna moved to a more populated area of Pennsylvania, where Benjamin died in 1852. Anna died in 1864.

That’s as far as I’ve gotten down the rabbit hole so far. The next son in the paternal branch, Great-Great-Great-Great-Grandpa Russel King Homer, is a doozy. With 138 extensive records on his page, it seems Russel was the one who took the Homers west across the Plains to Utah. He looks pretty fierce, doesn’t he? Where will this adventure take me? Stay tuned?

Wonderful information. My ancestors too x

We share the same family tree until Russell Homer. My several-time great grandfather is Benjamin Homer who remained in Illinois and Iowa after Joseph Smith Jr was murdered. He eventually joined the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints with Joseph Smith 111 now the Community of Christ. He married Sarah Lane and she eventually went to Oklahoma following his death.

I appreciate you sharing our history. Although I knew several of Russell’s stories, I learned more from your accounts. Thank you!