“Every day feels like living in a French surrealist film,” Beat said earlier this week. I perked up at his statement, as my morning browsing had left me thinking about the post-WWI Dadaists and how they had been right all along. Right to reject the dogma that marches blindly into devastating wars and create art that celebrates the irrational and chaotic — the tangled roots of truth and beauty.

I promise I’m not a doomscroller anymore, but I do indulge in many Substack newsletters that comment on current events. Nearly every day, there’s another featured news item that’s not only a disaster for a fair percentage of humanity but also profoundly stupid. I just … I just can’t with being a human this week, you know? We’re embarrassing. I wanted to apologize to the silly turkeys shamelessly flirting in front of our door cameras. I watched them strut about without self-consciousness and was reminded of a line from “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:”

“Many were increasingly of the opinion that they’d all made a big mistake coming down from the trees in the first place, and some said that even the trees had been a bad move, that no one should ever have left the oceans.”

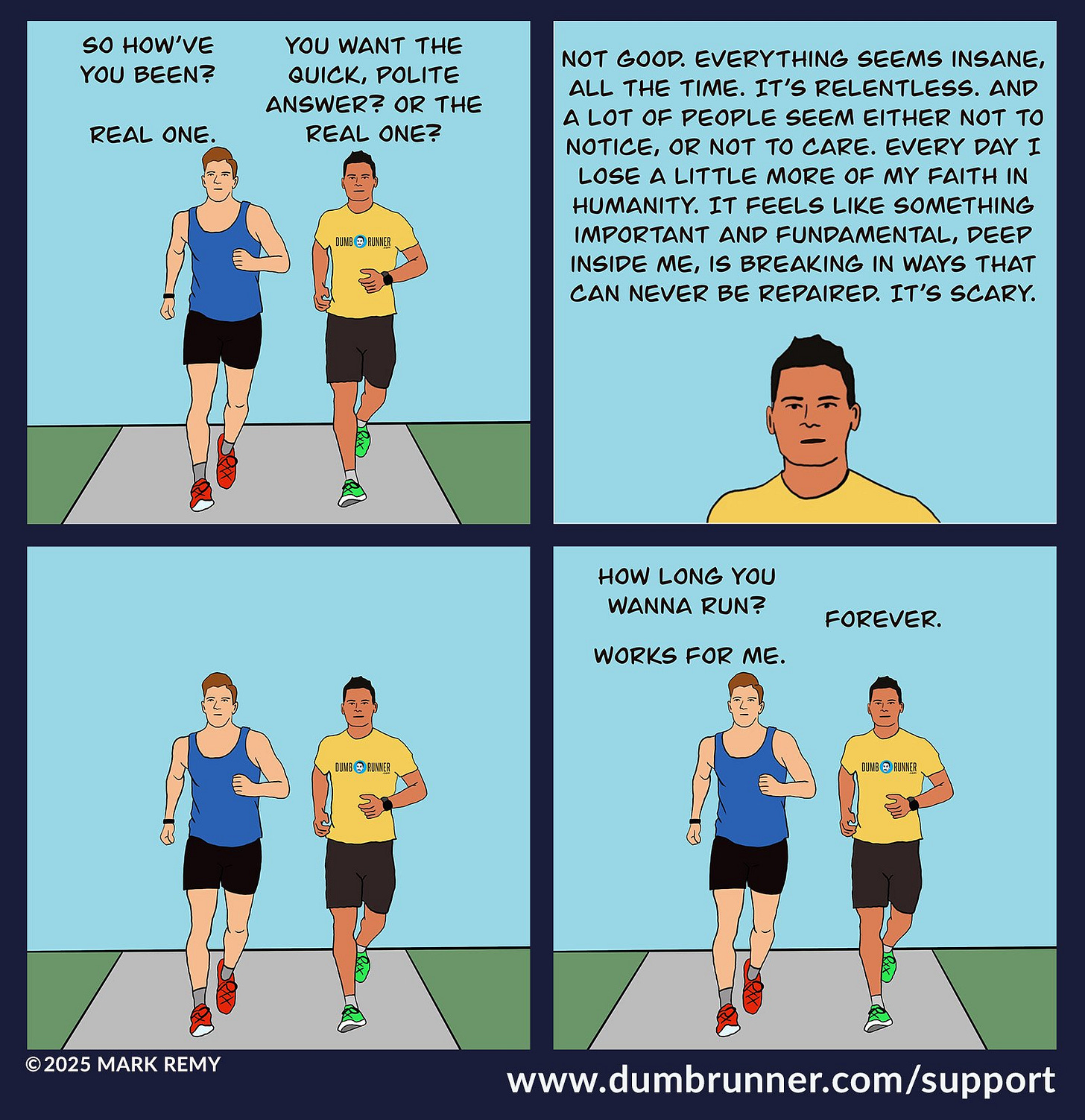

And then there was this heart-rendingly relatable cartoon from the always brilliant Mark Remy of Dumb Runner, whose humor transcends running and who deserves our support.

If I were a Dadaist, my masterpiece would be running forever … or until I dropped dead of exhaustion, which would obviously come first.

In my slow taper off of an antidepressant I’ve taken for more than two years, I finally reached zero milligrams last week. Can you tell? I intend to write about my experience once my brain has had more time to settle; it’s still quite new. But each time I’ve adjusted my dose by the tiniest increment, I have a lot of vivid dreams and feel more daytime anger.

The dreams and anger tend to settle down after a week, so I am hopeful I’m through the worst of it. Still, this week has been a barrage of unsettling dreams. I dreamt about how none of my friends even like me, about my Dad seemingly not noticing a very small-statured me talking with him as he gets ready for church, about buying a run-down Alaska wilderness lodge and committing to remodeling it as an AirBnB, and about a glacier in Juneau.

In that last dream, I was running across a frozen Mendenhall Lake while being stalked by a wolf. This dream mirrored real experiences I had while living in Juneau in 2008, when I rode my fat bike near Mendenhall Glacier with occasional sightings of a lone black wolf that locals called Romeo. But the dream had a more sinister edge: A wolf was stalking me in the shadows, I was running for what felt like my life, and when I glanced toward the glacier, it was gone — an empty, gaping gorge where the ice used to be.

While none of my “bad friend” dreams featured my friend Betsy, they seemed based on real guilt I’d had about not being there for her as she copes with the odds-defying late stages of brain cancer. A few months ago, I offered to join her on a dream trip to Alaska, where she plans to float in small boats on the Prince William Sound in June. With her neurological symptoms and fatigue, she will need a supporter to assist with the travel. But as the weeks passed, I became more uneasy — admittedly about the state of Betsy’s health, but also about my paralyzing fear of water that has proved to be an insurmountable mental wall during every float trip I’ve braved in the past 20 years. I expressed my concerns to my therapist. We went through a few EMDR sessions, and each time, simply imagining the trip devolved into worst-case scenarios and near-panic attacks. But every time I tried to talk to Betsy about this issue, it turned out to be a bad day for her symptoms, and we couldn’t meet. I confided in another friend, who offered to take my place. I was in London when I finally confessed my shortcomings to Betsy in an e-mail. She was gracious and understanding. But when she again turned me down for a visit after I returned to Boulder, I lapsed into a “bad friend” complex that manifested in nightmares.

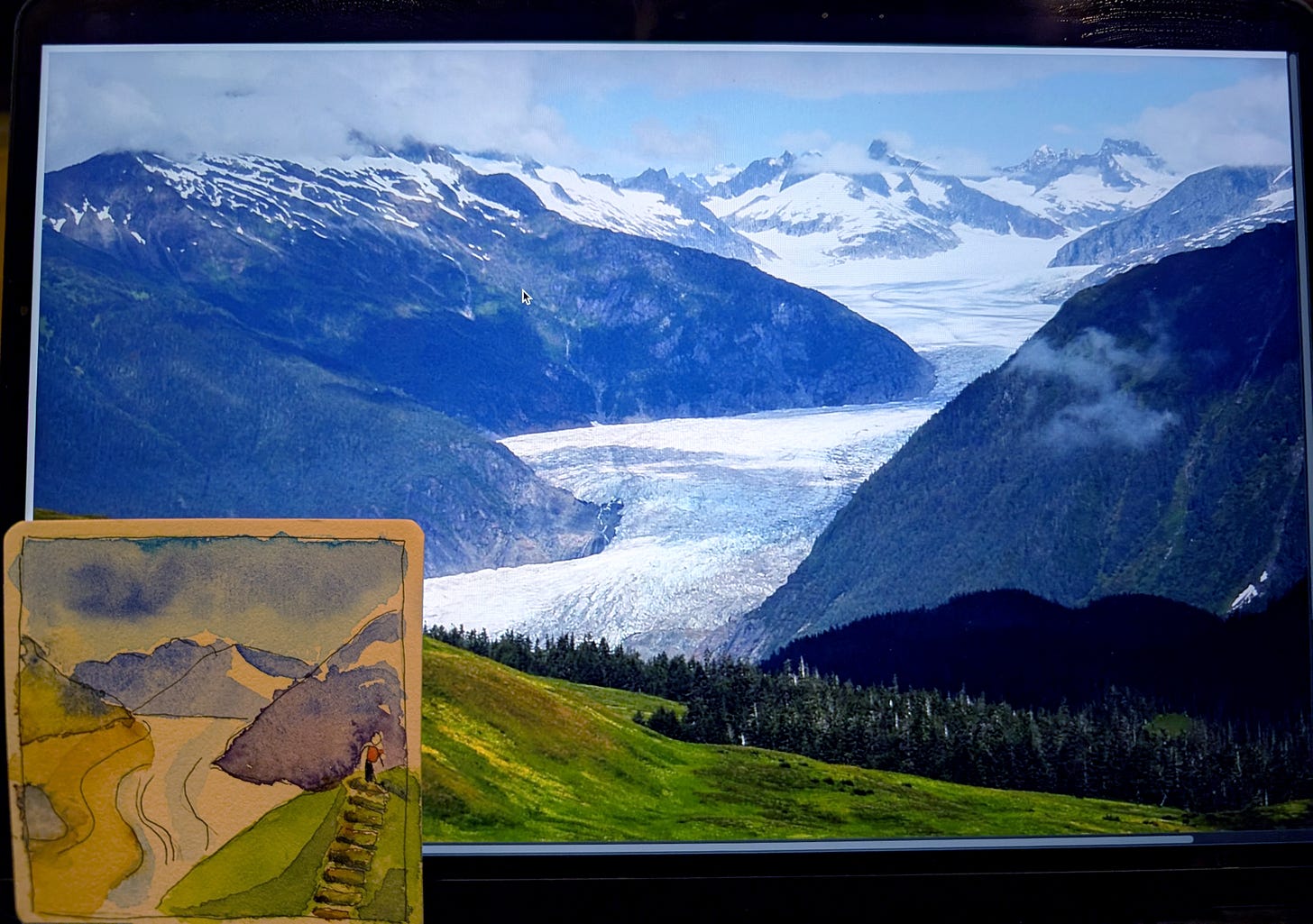

But the Juneau nightmare is what carried me into Monday. Betsy was finally up for meeting up with me, so we planned a short walk beside Standley Lake. As I walked through her door, she told me she had a surprise and enthusiastically presented the small square she’d spent the morning painting. Her eyesight has been drastically impacted by cancer infusions, so she used a magnifying lens to see the details.

For several seconds, I stared at the painting in quiet disbelief. Betsy had painted a glacier, and I thought it was the Mendenhall Glacier. The vantage looked like a high point from the west, perhaps Heinzelman Ridge — where, coincidentally, a friend and I came across the tracks of a wolf pack and the bones of a recently slaughtered mountain goat while winter hiking in 2009. I still shiver when I think about those bones.

My thoughts had started to unravel as Betsy prompted me to guess the scene of the painting … how did she know? Did she have the dream about wolves? Before I could venture a guess, she told me to turn the card over. I admit I was surprised — though it made perfect sense — to see a lovely thank you note and a title: “Mer de Glace.”

Mer de Glace — “Sea of Ice” in French — is a glacier located on the northern slopes of Mont Blanc above the Chamonix Valley in France. It was, and perhaps still is, the second-longest glacier in the Alps behind the Aletsch Glacier in Switzerland. Betsy chose this scene because she knows the French Alps are meaningful to me. I was touched. Here, too, I’ve stood at a vantage that mirrored Betsy’s whimsical painting:

I was thrilled that Betsy was not angry with me. So not angry that she battled her fatigue and vision difficulties to create this thoughtful painting. But I admit, my delight was tinged with a lingering sadness. Like Mendenhall Glacier, like all glaciers, Mer de Glace represents a sense of accelerating loss. I first visited Mer de Glace in 2012, when ice still filled the lower gorge. In 2015, my parents and I descended the long staircase that ticked off hundreds of feet of ice lost since the early 20th century. Return visits in 2018 and 2019 revealed a visible loss from 2012. The glacier loses 4-5 meters of thickness every year, and the melt is accelerating. I haven’t ventured back to the fading Sea of Ice since 2019. I haven’t had the time, but more than that, I haven’t had the heart.

My time with Betsy echoes this fear of loss. The glaciers will fade from this world, and so will I, and so will everything I love. But what’s meaningful, I know, is that it hasn’t happened yet. When Betsy and I walk, we stop to observe the flowers. We listen for the songs of meadowlarks. We watch the mallards dive beneath the calm surface of the lake. We talk about rowing. I love rowing, I tell her, but only on land — at the gym, on a rowing machine. I love tearing myself apart in the best full-body cardio workout I’ve found. We laugh at this silliness because when Betsy and I walk, there’s no past and future, just a joyful present. It’s not until later that I remember the accelerating loss of time.

The world is so big and full of shadows. I have reservations about inviting the anger and despair back in when something happened in January that gifted me with a soothing ability to not care. But apathy is not the point, is it? Since I’ve been thinking about the French absurdists, I’ve returned to some of my favorite essays from Albert Camus. Camus reminds me that the point of life — and its ongoing challenge — is simply to stay alive. But part of staying alive is refusing to concede to numbness. The point of life is to be awake to the experience of living.

“Get scared. It will do you good. Smoke a bit, stare blankly at some ceilings, beat your head against some walls, refuse to see some people, paint and write. Get scared some more. Allow your little mind to do nothing but function. Stay inside, go out - I don’t care what you’ll do; but stay scared as hell. You will never be able to experience everything. So, please, do poetic justice to your soul and simply experience yourself.” (Albert Camus, Notebooks 1951-1959)

The day before I went for a walk with Betsy, I embarked on a solo long run. Beat has a work trip to California coming up, and we took advantage of this opportunity to sign up for a 40-mile trail race in Napa on May 17. Since I injured my shin in the White Mountains 100 in late March, I haven’t had many opportunities to, ahem, train … and now spring allergies have filled my lungs with heavy inflammation. I don’t expect to notch a good performance in this race, but I know I can do it and have fun in the process. I’m grateful to be uninjured. It feels like a superpower — the ability to run for as long as I want. Not because I’m at all special or because I believe running increases my value as a human … maybe it would increase my value if I were a mule deer, but even the best human runners are terrible compared to a mule deer, and anyway I’m not delusional. No, running feels like a superpower because it’s a simple and nearly always available path to the closest I’ve felt to enlightenment. Running demands presence and awareness. It keeps my eyes open to the moment. It forces my little mind to do nothing but function.

May 11 was just six days out from this race, so a 34-mile training run on the hottest day of the spring so far was quite a bit of overkill. But I wanted to do it, so I did it. I set a route traveling west from my house along little-used trails through the wooded hills. I listened to music. I looked for signs of spring. I thought about my strange dreams and the news articles that made me mad. Then the trail wended through tricky boulder fields that required my full attention, so I let these thoughts go. I rejoiced in bursts of energy offered by delicious gummy snacks, the elixir of life. I wheezed and struggled, but I didn’t stop moving. I remembered to breathe.

I suppose this is the push-pull I’m in right now: Grieving things I haven’t yet lost, like glaciers and American democracy, but also feeling intensely grateful for the simple things, like running and time with my friends. As life feels increasingly surreal, I’m grabbing for any anchors I can find to stay grounded on Earth.

Love this-terrific writing. I think it may have uncovered important memories of my life. Sitting here avoiding the slogs of work and just reading a great piece!

I relate to a lot of what you wrote (well, not the specific weird haunting dreams, but the other parts!) and love the Remy cartoon too. Take care & enjoy a day of nothing but running around Napa!