Three days after the accident, Search and Rescue returned the contents of Dad’s backpack to my mom. The remnants were Classic Dad: a paper map of the Wasatch Mountains that was decades old; an equally ancient first-aid kit; a deflated mylar balloon that he picked up somewhere high in the mountains and tied around trees to mark faint intersections; the SPOT unit that Beat and I gave to him for his birthday one year so he could send “I’m okay and having the time of my life” messages during his solo hikes; his square plastic water bottle.

“Where’s his backpack?” Mom wondered. Where were the brand-new hiking boots that he had just bought at REI?

“They don’t return clothing,” I replied flatly while trying to banish the mental image of the tattered condition of those things. Quietly, I wondered about Dad’s blue jacket. That, too, was missing. He must have been wearing it when he fell.

We only received two of the items he had been wearing at the time of his death: his wedding ring, which we were grateful to see returned to my mom; and his GPS watch — a Garmin Forerunner 910XT which was my GPS watch until I gave it to him a few years earlier. Dad enjoyed tracking how far he’d hiked and how many feet he’d climbed. He’d look at the numbers at the end of the day, smile, and turn off the watch — he never once downloaded the stats or stored them in any database. I spent years trying to convince Dad to sign up for Strava or care about personal bests, to no avail. Dad simply wasn’t achievement-oriented. He sought experiences. The rest was incidental.

Mom handed the watch to me. “This is yours, isn’t it?”

“Well …” I trailed off. I clasped the black band. The screen was badly scratched. When I pressed the power button, nothing happened.

Initially, I thought the watch might have been broken in the fall. Later, after Beat returned home following the funeral, he plugged in the watch and was able to start it up. Per my request, he looked at its final track.

“It pretty much tells the whole story,” Beat told me over the phone. “You’ll probably want someone with you if you want to look at it.”

I didn’t want to look at it. I returned home weeks later — having been largely unsuccessful in my mission to help my mom sort out her new life — and stashed the watch in the back of my miscellaneous drawer. The other mementos I brought home with me — his fanny packs, his ancient paper maps, his hiking hat, his balaclava and crampons, his neon orange shirt — I lovingly placed in a memorial space upstairs. But the watch didn’t feel like it belonged. The watch felt like something that was my fault. “Dad wouldn’t have wanted to record that.”

Rescue #27: Fallen hiker

Callout Time: 2:43 PM 6/16/2021

Duration: 3 hours 10 minutes

SLCSAR was called out for a fallen hiker on Mount Raymond. Two hikers were coming down from the summit of Mount Raymond when one slipped and fell down a steep slope into Mill A. When his partner was able to make it down to his friend he found that he had sustained major head trauma and had died in the fall. SLCSAR sent 3 teams up the trail to help the surviving party out and help with the body recovery. The Department of Public Safety helicopter was also called to help and was able to recover the body and the surviving member. Both hikers had hiked the peak multiple times and were on the summer trail from Baker Pass. RIP.

Raymond was one of Dad’s favorite mountains in the Wasatch Range. It’s one of the twin brother peaks (both are 10,240-ish feet) that reside on the ridge between Millcreek and Big Cottonwood canyons. Raymond and Gobbler’s Knob are a hiker paradise, offering thousands of feet of vertical relief over their drainages, sweeping views, and countless variations of approaches for big days, short days, hard days, less hard days, winter days, and creative exploratory days.

On June 16, 2021, Dad told my mom that he had his friend Tom were going to climb from Butler Fork and try to descend the south ridge of Raymond. If that technical ridge didn’t go, they’d turn around and return the way they came on the summer trail. It was all simple, nothing too new, and Dad was always one to play it safe — he was never afflicted with summit fever or thrill-seeking tendencies. Mom was perplexed when he didn’t return promptly at dinner time. It wasn’t like Dad to be late. She waited and finally started cooking, knowing that when he came home, he’d be hungry. As the pan heated up, Mom received a knock on the door.

Later, Tom told me that he and Dad scrambled a short distance down the south ridge before deciding it was too sketchy, then turned around. They returned to the summit and descended Raymond’s “summer trail” along the still-sharp north ridge. Tom was a short distance ahead when he heard a gasp, turned around, and watched Dad fall. Tom scrambled a few hundred feet down the slope, called for help using Dad’s SPOT unit, and waited for several hours until Search and Rescue arrived. I never received more details from Tom besides this assurance: “I can give you the comfort of knowing, that the way it happened, it was over quickly and Jed did not suffer.”

I didn’t want to know more than that. And yet, not knowing haunted me. Where did it happen? Why did it happen? How did it happen? Dad knew this mountain so well. And there was only one short section that was exposed — at least exposed enough to cause a fall like the one Tom described. Dad would have been careful in that place. But was that even the place? It might not be. Freak accidents happen. It’s difficult to accept, but it can happen to anyone. It could easily happen to me.

I wondered if that knowledge, in part, is what haunted me. I have so many accidents. I could catch a toe and be gone in a momentary lapse. Still, it’s easier to accept that I could lose myself this way than to acknowledge I lost my steady, stalwart, strong-as-an-ox 68-year-old father in just such a lapse.

In June, my two sisters, my mom, and I gathered to mark the second anniversary of Dad’s passing. The sisters and I found a measure of peace in visiting our hiker father’s favorite places. I guided Lisa on her first summit of Gobbler’s Knob, a peak Dad and I climbed together at least a dozen times. She asked me if I thought I’d ever visit Mount Raymond again.

“Probably,” I replied. “But not for a while.”

Still, that visit rekindled my unrest. Two years had passed and I still couldn’t push the questions away. How did it happen? Why did it happen? I had to accept that the “how” and “why” would forever be a mystery. Still, I had evidence of the “where.” Maybe … maybe I could find a measure of peace in knowing that much.

On June 23, Beat was away at a race and I was tossing and turning in bed at home. I could almost hear the ticking of Dad’s watch … my watch … even though it had never had such a function and had been dead in a drawer for two years. Would the watch even charge up again? I needed an ANT stick to download its contents … could I even find one? Well after midnight, I finally rolled out of bed and pulled the scratched and dusty watch out of the drawer. I rifled through Beat’s stuff for nearly a half hour until I found an ANT stick. Then I connected the watch and its charger to my laptop. Another half hour passed before it was finally charged enough to start uploading data. When it did, it started with activities that happened years earlier. 2019, 2020 … Dad had never uploaded or deleted any of it. Dozens of hikes started appearing on my Strava account. I was going to have to delete them all. Before I did, I examined each of the activities. I couldn’t help myself. It helped me feel close to him.

“November 29, 2019. That was the last time we did Gobbler’s Knob together.”

“I didn’t even know there was a trail there. Maybe there’s not.”

“Wow, PR? Dad’s faster up Red Pine than I’ve ever been!”

Finally, another hour had passed and the night was well into the wee hours when the watch arrived at its final entry — 8:56 a.m. Wednesday, June 16, 2021.

Distance: 8.57 miles. Elevation gain: 3,425 feet. The red line on the map did indeed tell a story. I saw where Dad and Tom hiked beyond the summit: squiggly lines, 40% grades, and paces registering at 0.5 mph. After a quarter mile, they turned around and returned to the summit. Another quarter of a mile later, the track veered sharply off the ridge with speeds in excess of 30 mph. Dad left the ridge at 9,711 feet elevation and stopped 17 seconds later at 9,333 feet— a 400-foot fall. From there, the track spent the next four hours bouncing in place before making a swooping curve down to the canyon at 7,177 feet — the helicopter rescue. Then the track disappeared into a void before briefly sending one more point from my mother’s home days later.

One might think it’s upsetting to know all of this, to write it down. But the data is something real, a piece of the story that is tangible and immutable. For all of the unknowns, it’s one thing I can know. That does bring me a measure of peace.

I downloaded the gpx file, named it “Dad’s Run” and saved it to my own GPS device in a folder of tracks I will never delete.

On Aug. 23, I again traveled out to Salt Lake to visit my Mom. I’d made all of these plans that extended from hiking with my sister in Utah to spending half of September climbing every mountain I could manage in the Alps. So, true to the klutzy side of myself of which I am deeply suspicious and afraid, I lost my footing during a spontaneous, hour-long trail run and injured my arm. I thought my elbow was broken, enough so that I sought out an Urgent Care. The joint wasn’t broken, but it was badly swollen and painful. I wrapped it, switched from two hiking poles to one, and decided it was just another one of my klutzy blunt-force injuries — of which I’ve had many in the past year — and didn’t need to slow me down.

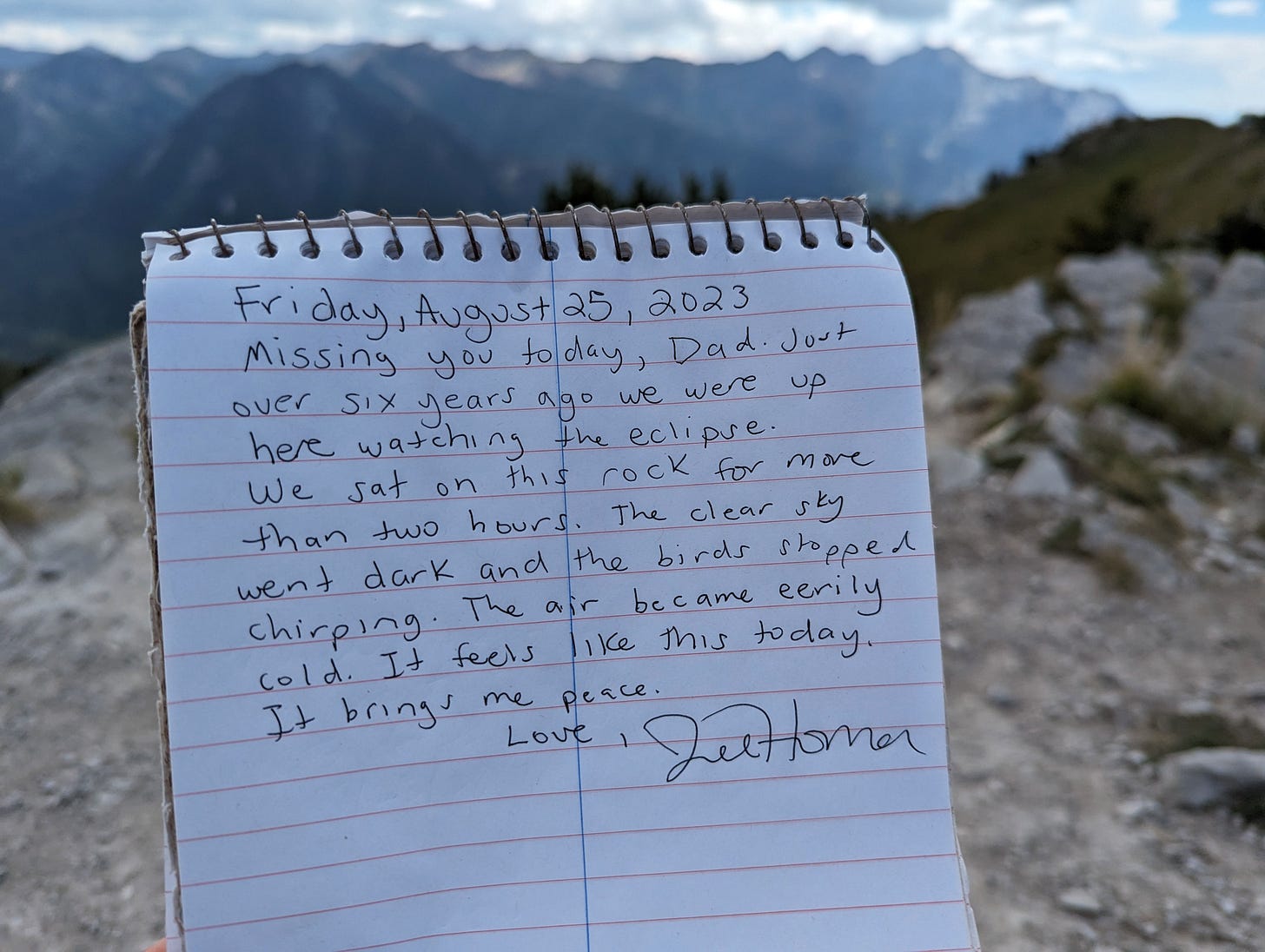

Two days later, I was sitting at the breakfast table with Mom and talking about my plans for the day. I told her I wanted to hike to Gobbler’s Knob. This is the summit I’d doubtlessly visited the most with Dad, and I’d recently been reminded of the day we spent two hours on the peak waiting for the solar eclipse — Aug. 21, 2017. This was practically the anniversary — just a few days late. Talk of Gobbler’s Knob invariably brought up Mount Raymond. Somehow, the question of “where it happened” came up. I told Mom that I knew the answer because I had Dad’s watch, which likely stored the GPS track. I told her that I wanted to visit someday and wondered if she’d be upset by that.

“No,” she responded, her voice wavering a little.

I wasn’t convinced. Still, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I set out for Big Cottonwood Canyon, making a quick stop at Smiths on 1300 East to buy a sandwich. This was the grocery store where we often shopped when I was a small child. I have vivid memories of riding through the aisles at the bottom of the shopping cart, trying to grab cereal boxes without her knowing. I remember waiting in the car while my mom darted inside for a minute. I remember trembling. I had such separation anxiety back then. I still have similar fears now. The Smiths storefront has hardly changed. Inside, shoppers are greeted by a floral display. I don’t remember if it was always like that, but the display caught my eye. I scanned the bouquets, thinking, “It would be nice to bring some flowers to Dad … to his final resting place.”

Something in my mind started to hum, moving my body in almost a robotic manner. I never exactly made a decision to visit Mount Raymond. I simply understood that this was the way. I circled the floral displays multiple times, picking up bouquets and putting them back. Nothing seemed right. They were too gaudy, too cheery, too try-hard. They didn’t work. Then these simple white flowers caught my eye. The entire bundle was on sale for 50% off, just $3.99. For Dad, this seemed fitting. I felt a rush of nervous anticipation.

The robotic movements continued — my mind humming, my body responding in kind. The climb to Mill A Basin is relentlessly steep, and my arm had been hurting so much that it kept me awake for much of the previous night. Here I felt no pain, no fatigue. Temperatures were mild and a light breeze cooled the sweat on my face. Aspen leaves fluttered, filtering the morning sunlight. The air had a honey-like sweetness from a burst of yellow wildflowers.

Dad’s “final resting place” is about a quarter mile from the Desolation Trail, 300 feet up the steep basin. Because of GPS wander, I can never be 100% certain where it is. But most of the points were at a boulder that rested alone in a field of wildflowers. Because of physics — but also aesthetics — I decided this rock was the place. This probably sounds strange or morbid — that I wanted to visit the place where my father’s body came to rest after he fell 400 feet off a mountain, where Tom had to wait beside his lifeless friend for hours before rescuers arrived. But I found peace in this place. It was so beautiful in spite of — or perhaps because of — its chapter in my family’s history.

“I’m so glad you weren’t there,” Tom told me once. I agreed. That too is something I think about too often. What if it had been me in Tom’s place? That’s a trauma I fear I couldn’t survive, that I’d rather not survive. There will probably be traumas of similar magnitude in the future. How do we ever get past the pain? How do we go on just … living? Here at this limestone grave site, I could almost hear my Dad’s confident assurance. “We just do.”

I looked toward the slope marked with a straight line on my GPS. It was nothing like I had imagined. It wasn’t cliffy or jagged or fearsome. It was a gentle — albeit 40-degree — mountain chute filled with wildflowers. Ever since I acquired the watch, I’ve had this fantasy about locating something of Dad’s that has been lost since 2021 — his trekking poles or his glasses. Perhaps his blue jacket. As unlikely as it would be to locate these things even if they were still up here, I could never shake the thought. When I looked up the slope, my brain hummed matter-of-factly: “You can climb this.”

True to the capricious side of myself of which I am deeply suspicious and afraid, the climb was a bad idea. The angle of the chute became steeper as I approached the ridge, and the footing was tricky on loose dirt covered in vegetation. The use of both hands became necessary to grab what I could for leverage. My injured elbow seemed to scream at me. “Stop it! Stop it!” The pressure from grabbing sent electric shocks of pain through my entire arm. Finally, the dirt beneath my feet became too steep and loose, and I had to climb up onto the jagged limestone ridge. It wasn’t a difficult scramble, but my arm was beginning to disassociate from the pain, and felt weak. I feared my still-injured hand (the tendon I tore in May. Same arm) was going numb. And I knew it was possible to fall to one’s death from here because … I knew.

“If I fall from this ridge my family is never going to forgive me,” I thought. But that was the closest I came to a negative thought. Even amid the pain, I continued to think, “It’s all right. It’s going to be all right.”

I clasped my good hand around a final handhold and pulled myself up to the edge of the knife ridge. My heart was pounding from the frantic scramble and I felt dizzy, so I clasped both arms around a gnarled pine tree that was clinging to the ridge for its own life. As I paused to catch my breath, I gazed at the surrounding trees: all ancient-looking, all bent and twisted, some charred and missing most of their top halves from years — likely decades — of survival amid lightning strikes and gale-force winds and blizzards at 10,000 feet.

When my heart rate settled, I knelt down and pulled my GPS out of my pocket. The track led to here — to this exact spot. For some time I had been climbing where I thought I could safely ascend rather than following my device, so I was surprised that I hadn’t deviated from the line. I kept my good hand clasped around the tree and touched the spot with my painful hand. Electric shocks again reverberated through my core. It was the exact sort of place I could see myself catching a foot — a small gap in the rock, likely hidden if you’re not looking directly at it. One minute I would be on top of the world, taking confident strides down a mountain I’d climbed countless times, and the next …

It was strange to find the exact point where Dad fell. It was as I had long imagined it, which in itself was odd given I’d only been to this summit once before. The story I arrived at — about catching a foot, a common mishap in exactly the wrong spot — was the same story I had been telling myself for two years. I still didn’t know whether this story was the truth. And yet I felt serenity from my discovery all the same.

“He just tripped and fell. There was nothing malicious about it, nothing reckless. It wasn’t a bad decision. He just tripped and fell.”

Life is so fragile. How many times have I just tripped and fallen? Maybe that’s what will get me someday. Maybe it’s likely that’s what will get me someday. But not today. Not today. How do we go on just … living? We just do.

I continued toward the summit. Despite ongoing scrambling, the robotic spell returned and the pain in my arm subsided. The summit of Mount Raymond was incredible. The air was so pristine I could see past the Oquirrh Mountains. Mountainsides brimmed bright green, also an anomaly so late in the summer. Although there was probably more snow at the time, this could be very similar to the view my father saw in June 2021. His last view. He would have been so happy here. That was the story I told myself, but it was also something I knew beyond doubt.

I sat on the summit for a long time. I placed the last of Dad’s bouquet on a rock. I had expected to cry but didn’t. I only felt peace. The breeze eventually brought a mild chill, and I remembered that I would have to tell my mom and sister that I had come here. That snapped me out of my reverie. I looked at my watch and thought, “But there’s still time.”

Gobbler’s Knob had been my original plan, and given the still-meaningful anniversary, I didn’t want to miss it. I turned away from Raymond — the mountain I could now look at without malice — and continued toward Raymond’s brother — the mountain for which I have only ever felt gentle affection. I climbed hard without feeling pain or fatigue until I practically collapsed at the summit. I signed the summit register and sat for another indeterminately long stretch of time. I was alone, and yet I didn’t feel alone. I didn’t feel alone anymore.

August 21, 2017. I was set to drive home to Colorado after a brief trip to Utah to attend a funeral for my Aunt Jill. My aunt by marriage, she shared my name — Jill Homer. She died after a years-long battle with blood cancer. She was just 53 years old. Her death shook me in ways I hadn’t expected. She was the type of person who was genuinely, selflessly good. And she was so young. Her children — my cousins — are all younger than me. How do you cope with losing a parent when you still have so much life ahead? How do we just go on living?

Dad reminded me of the solar eclipse set to happen early that afternoon. Since I wouldn’t be in the path of totality, I hadn’t made a big deal out of watching it. But Salt Lake still sat in the 90-percent-totality range. It would still be pretty neat to see, Dad reasoned. Despite a tight schedule, I decided I could spare a half day to hike to a summit and watch the eclipse with him.

We chose Gobbler’s Knob, of course. As we climbed, we talked candidly — me about the health issues I’d been struggling with that year, him about his grief for his sister-in-law. We ascended the mountain much faster than either of us expected and arrived at the summit more than an hour early. I’d never lingered so long at a peak. It was odd — and gratifying — to just sit and one place for so long and do nothing but observe my surroundings. There was so much to see.

As the time approached, Dad donned his eclipse glasses. I giggled like a little girl, seeing my Dad in funny glasses. We watched the moon slowly take a large bite out of the sun. But what was more unique — to me, at least — was what happened to the world as the sun disappeared. Everything became increasingly still and quiet. Bugs ceased buzzing around us. Nearby birds briefly panicked, chirping up a storm before they, too, went silent. Even the wind calmed. An eerie twilight settled over the landscape, casting the mountains in a surreal bronze alpenglow. A chill swept over the hot August afternoon, as though something had turned off the sun. Which … something had.

“Are you cold?” Dad asked as he turned toward me. I was shivering. I hadn’t noticed.

“A little,” I admitted.

Dad reached into his backpack, pulled out his blue jacket, and handed it to me.

“Are you sure?” I replied. “You don’t need it?”

“I’m fine,” he answered matter-of-factly. Whether this statement was true, I couldn’t know. Dad almost never admitted to discomfort or pain. But he would leap to action in an instant to ensure the people he loved never felt discomfort or pain.

I wrapped the jacket around my shoulders and relished the warmth and love of the moment. I would never need anything more than what I had right here. If only it were possible to pause at a moment in time for eternity.

Instead, the world keeps spinning. The moon moves past the sun and the light returns. The fragile, fleeting nature of it all is what makes each moment so magical.

This is beautiful, thanks for writing it 💜

This gave me chills, goosebumps, tears, but even a feeling of the peace you felt on this journey. I can’t imagine how such a journey would feel but you captured it so eloquently and beautifully, as always. Thanks for sharing this.