Thumbing through my middle-school journals for the first time in at least two decades, at the age of 42, has caused a visceral reaction I wasn’t expecting. What I expected was to laugh and bask in warm nostalgia. What I’ve experienced is a regurgitation of the insecurity, confusion, and humiliation that was so close to the surface when we were still figuring out our way in the world (or at least when we still believed we would eventually figure out our way in the world.) And what’s surprising has been the lucidity of these emotions, now decades-old and long-digested. I find that I need to put the journals down and walk away, maybe pull up a Doomscrolling app to jolt myself back to the present.

My “middle-school journals” are more extensive than I remembered. There are four volumes that start in 1987 and end in the fall of 1994. The entries stop rather abruptly in October, with my 15-year-old self declaring, “My life is boring. I don’t think I’m going to write here anymore.” This silence might have continued well into adulthood if it wasn’t for a grizzled veteran English teacher who was nearing retirement. (He was an actual veteran. I believe he served during the Korean War.) Mr. Mercer had each student write a personal journal entry — which he was never going to read — as a way to distract the class for 15 minutes every day. I embraced this time-killing assignment, which eventually bled into years of notebook chronicles clipped into three-ring binders. But this was still a few months away.

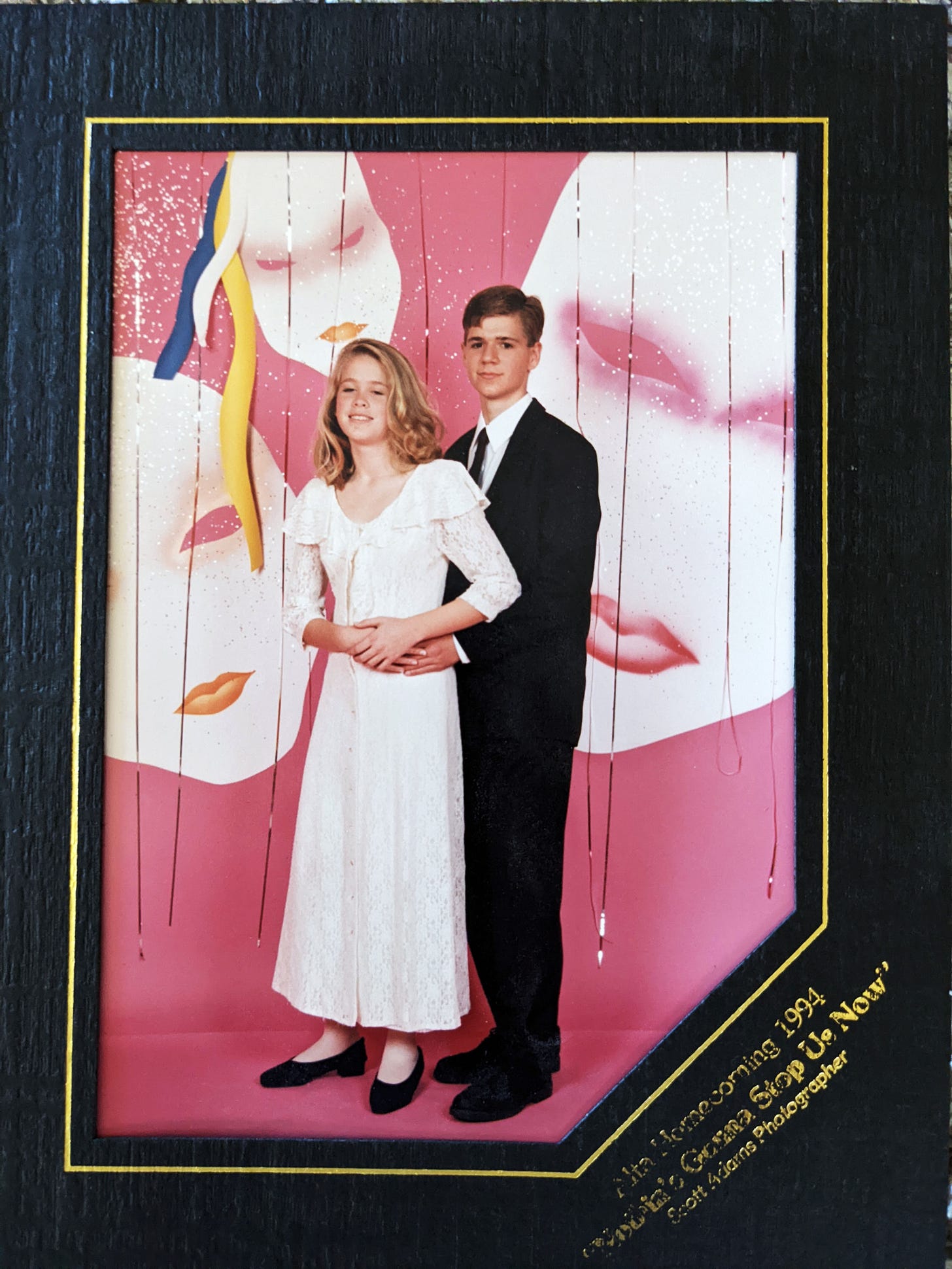

One of the final entries in my hardbound volumes did evoke a smile — along with the requisite cringing. Scrawled in red pen and dated October 1, 1994, the entry begins, “Guess where I went today? Well, I shouldn’t start it like that, just in case my family reads my journal someday, but, against the knowledge of anyone in my family (as far as I know), I went to Homecoming!”

Yes, I lied to my parents and snuck out of the house to go to … a Homecoming dance. It’s become one of my sisters’ favorite stories to cite whenever the subject of teenage rebellion comes up. I had just started my first year at Alta High School as yet another pale-faced sophomore in a student body of more than 2,000 suburban teens. The school was so enormous that there were cliques within cliques. The anonymity could be excruciating. I just wanted to find a place where I could stand out.

A boy from my neighborhood asked me to the Homecoming dance. In Utah, at least in the 90s, school dances were the foundation of the social hierarchy. If you had any clout at all, you’d be at these dances, unless you were a burnout, a weirdo, or a loser. Side note: As I matured, I embraced the “weirdo” label and mostly shunned school dances. But as a baby sophomore, I still clung to junior high dreams of conventional popularity. I had to go to this dance.

The problem? I was 15 years old. My family strictly adhered to tenets set by our church, which stipulated that youths should not date at all until they turn 16. Of course, I’d already pushed the boundaries of this rule — flirting with boys at the mall, holding hands at the skating rink, etc. — but I had never been on an official date. And I knew my parents weren’t going to crack for this one either, so I kept the invitation a secret. I told the boy “yes” and began scheming my jailbreak.

This is the part of the story that my sisters love, because a Utah high school Homecoming dance is such a squeaky clean event to sneak off to. I told my parents I was going to the movies with a girlfriend. I’m sure they were a little confused when I prepared for the evening by attempting to curl my hair, which was something I didn’t typically do. Then I bid them goodbye, walked out the front door, and then climbed over a wooden fence to the backyard, where I had stashed my dress and shoes in our playhouse. I changed my clothes, climbed back over the fence, and huddled in the shadows next to some bushes until a green car pulled up to the curb.

The boy who’d invited me to the dance stepped out from the backseat, plastic box with a wrist corsage in hand, and started walking toward the porch. I tried to time my interception so it wouldn’t look like I had been hiding in bushes. When he had nearly reached the front door and his back was finally facing me, I darted toward him.

“Sorry,” I said breathlessly as he turned around. “I was just …. over there. I’m ready to go.”

This was the part I really didn’t plan well, as the boy — his name was Mike, and he too was an upstanding member of the LDS Church who happened to be 16 years old — expected a traditional meeting of my parents. He looked at me with a confused expression, looked toward the door, and then handed me the corsage. This is a particularly cringey part of my story because I was still ignorant about the purpose of corsages. I thought Mike was giving me a flower as a gift.

“Thanks,” I replied. “I’m just going to put this on the porch for my mom to put away,” and then I left it on the porch. Mike’s facial expression twisted even more, but he remained silent. Then, just as he turned back toward the car, I flicked the boxed corsage into the bushes like a frightened cat because I didn’t want my mom to discover it on the porch. Aarrrgh, aarrgh, why am I revisiting this part of my life?

Mercifully, Mike brushed off my unhinged behavior and continued his chivalrous gestures by opening the car door for me. Mike’s cousin and his date were in the front seats, and the four of us headed to a Chinese restaurant for dinner. I’m not sure how we ended up there because Mike didn’t even like Chinese food. He found fish sticks on the children’s menu and ordered those. The cousin, Charlie, was a bit of a wild child. Charlie filled the awkward empty space with tall tales of his escapades, which I remember vaguely as being gross and unconvincing, and which I described in my journal (inexplicably) as “old mine stories with all of these body parts.” All I can say now is thank God for Charlie; at least I wasn’t the only erratic weirdo in the group.

The night progressed more or less in the traditional way. Mike, I decided, was cute and tall and nice, but we weren’t well-matched. He was too much of a “cowboy” and I … while I still wasn’t sure where I fit in, I knew I wasn’t even a little bit country. Mike must have felt the same way because when Charlie pulled up to the curb and I darted out of the car, Mike didn’t even make a move to walk me to the front door.

Just days later, I stashed my journal away and kept this secret for a while. At some point, I confessed the funny story to my sisters. It wasn’t until very recently (and by recently, I mean less than a month ago) that the story came up again and I learned that my Mom never knew that I snuck off to Homecoming in the tenth grade. She was genuinely surprised … not so much by my sneaking off, but by the fact I went to Homecoming.

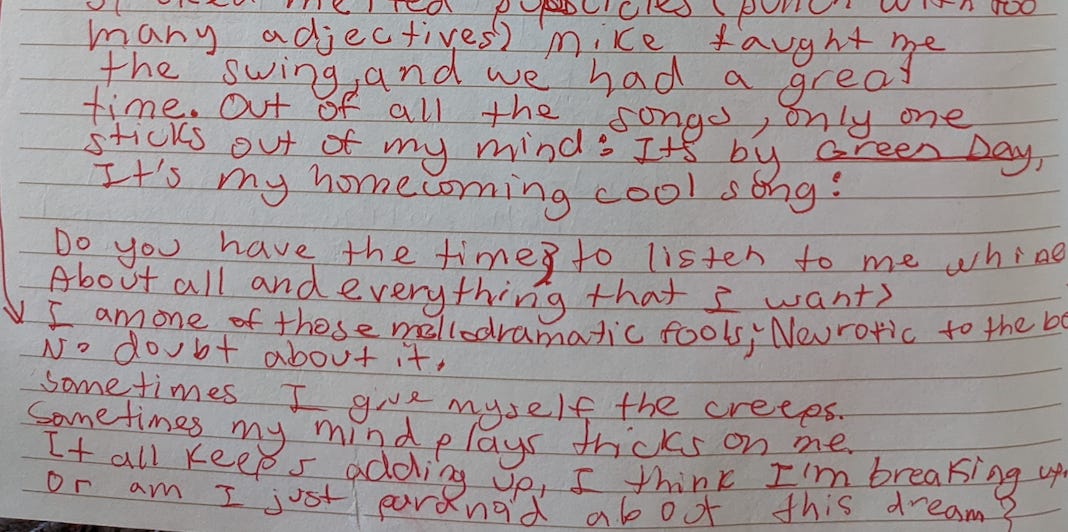

Looking back, I think the most influential part of the experience was hearing the Green Day single “Basket Case” for the first time and being mesmerized by the song. Charlie and I engaged in frantic dance moves which undoubtedly also did not impress Mike. But in this transcendent moment, I found the first meaningful spotlight on my path to a high school identity. In my journal I would call it “my homecoming cool song” and tried to recount the lyrics, which I got wrong in humorous ways:

“It all keeps adding up, I think I’m breaking up. Or am I just paranoid about this dream?”

Great story! Made me laugh, too. Agree with Andrea: "Your writing is amazing even outside the adventure genre!"

This is the best story I’ve read in a long time! It’s a dreary wet day here and reading this made me laugh. It’s so unbelievably awesome. Your writing is amazing even outside the adventure genre!

Thank you Jill!!

Andrea